January 1 feels familiar in India today, but it did not grow from our soil. It became the official New Year through colonial rule, when the Gregorian calendar was enforced for courts, taxes, land records, and administration. Following it was not a matter of preference. It was a condition for survival. Missing a date meant penalties, mounting interest, or even loss of land. Time itself was turned into a tool of control.

Long before this, the Hindu New Year followed nature’s rhythm. It arrived with spring, harvest cycles, and renewal, not with deadlines and paperwork. Colonial rule disrupted this natural relationship with time, pushing indigenous calendars to the margins and training generations to live by an imposed system. The way India marks the New Year today is not accidental. It reflects a long history of cultural displacement that quietly settled into everyday life.

What did the Hindu New Year represent before colonial rule?

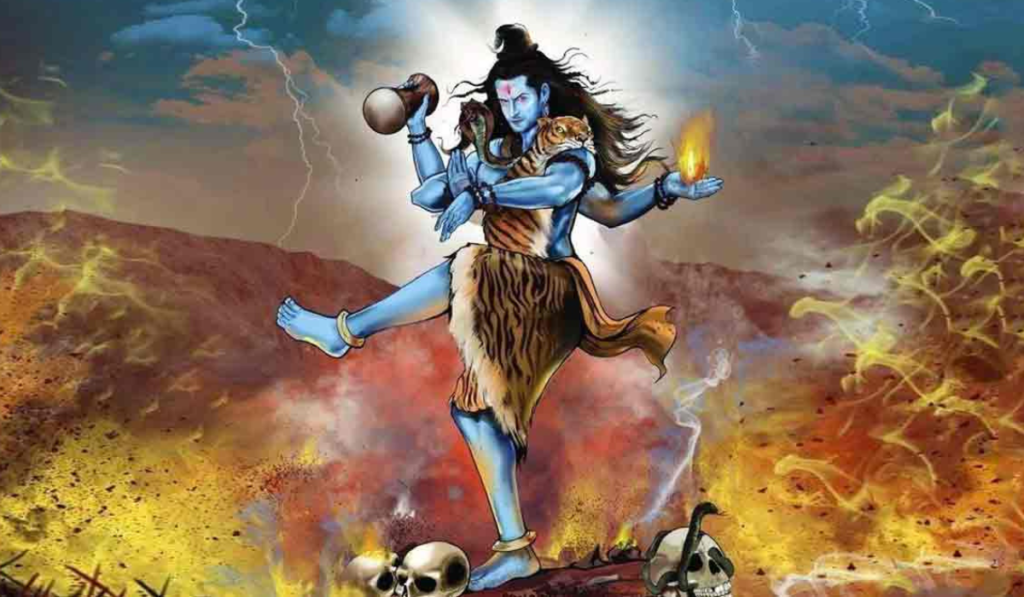

Before foreign systems redefined time in India, the Hindu New Year was not a date fixed on paper. It was a moment felt in nature. It began with Chaitra, when spring arrived, fields were prepared for new crops, and life visibly renewed itself. Time was observed, not imposed. Seasons, lunar cycles, and the movement of the sun guided daily life.

The Hindu New Year marked renewal at every level. Homes were cleaned, minds were steadied, and intentions were set through sankalpa. It was a reminder to begin again with discipline and awareness. Agriculture, trade, education, and spiritual practices all aligned with this cycle. Time was not something to race against. It was something to move with.

This understanding of time reflected a deeper worldview. Life was seen as cyclical, not linear. Endings naturally led to beginnings, and renewal was built into existence itself. The Hindu New Year was not about celebration alone. It was about harmony with prakriti, balance in action, and conscious living.

The Colonial Mindset: Disrupt the Cycle, Control the People

Colonial Mindset was simple: Divide and Rule. Not with violence but with planned strategic policies.

Colonial rule did not misunderstand Indian systems. It studied them closely and then dismantled them deliberately. British administration understood that Indian society functioned around natural cycles, especially agriculture. The Hindu calendar was not symbolic. It determined sowing, harvesting, trade, rest, and survival. To control revenue, this cycle had to be broken.

Mandating the Gregorian calendar was one of the most effective tools. Taxes were fixed according to foreign dates, not seasonal reality. A farmer was expected to pay revenue when, according to the Hindu calendar, the harvest had not yet arrived. No crop meant no income, yet the tax demand remained unchanged. Failure to pay invited interest. Interest invited legal action. Legal action often ended in the confiscation of land.

This was not accidental misalignment. It was annexation through administration. By forcing Indians to operate outside their natural economic rhythm, colonial rule ensured constant financial stress, dependency, and dispossession. Indigenous calendars were dismissed not because they were inefficient, but because they preserved autonomy. Breaking that autonomy was essential to colonial control.

The destruction of Hindu culture did not always happen through visible force. It happened quietly, through deadlines, paperwork, courts, and revenue notices. When time itself was taken out of the hands of the people, resistance became harder, and survival became conditional. This is how a civilisation was weakened without constant violence, by turning its natural order into a liability.

Why India Still Celebrates New Year on January 1?

British rule in India lasted for more than two hundred years. When the British finally left, they did not leave behind a thriving nation. They left behind a country drained of wealth, pushed into poverty, burdened with debt, and carrying the scars of wars it never chose to fight.

Millions of Indian soldiers were sent to die in World War II for an empire that was not theirs. Life expectancy hovered around thirty years. Famine, bankruptcy, and systemic exhaustion defined the so-called inheritance of colonial rule.

Along with this devastation, the British also left behind their administrative machinery, including the Gregorian calendar. It had already been embedded into courts, revenue systems, banks, schools, and governance. What had once been enforced through power now continued through habit.

January 1 survived not because it reflected Indian life, but because colonial systems were never fully dismantled. Indigenous timekeeping was reduced to culture, while the colonial calendar retained authority. This was not progress. It was the quiet continuation of control, long after the rulers had gone.

Is the Hindu New Year No Longer Celebrated?

No. It is still celebrated, only in different forms.

Across India, the Hindu New Year continues under regional names and customs. In North and West India, it is observed as Nav Varsh or Gudi Padwa with the beginning of Chaitra. In the South, the New Year arrives as Ugadi, Puthandu, and Vishu, each aligned with natural and solar cycles. Chaitra Navratri also marks this time of renewal through discipline and spiritual cleansing. The expressions may differ, but the essence remains unchanged.

What colonial rule removed from official systems survived within homes and communities. These New Years were never about grand display. They were about harmony with nature, livelihood, and inner balance. That is why they endured. The Hindu New Year did not disappear. It continued quietly, where tradition is lived, not declared.

Conclusion

Colonial rule did not only take land and wealth from India. It disrupted how time itself was lived and understood. By enforcing the Gregorian calendar, a natural, seasonal rhythm was replaced with rigid deadlines that served power, not people. What followed was not just administrative change, but cultural displacement.

The Hindu New Year survived because it was never dependent on authority. It lived in cycles of nature, in homes, fields, and temples. Remembering it today is not about undoing the present, but about understanding the past clearly. When we recognise how deeply systems shape daily life, we regain the ability to choose with awareness.

The Hindu New Year is not lost. It waits quietly, aligned with renewal, balance, and continuity, asking only to be remembered.

Let’s stay connected! Come say hi on Instagram or follow us on Facebook for more interesting knowledge.